Dr Who. She is a Time Lord with a friend who has dyspraxia. This isn't about Dr Who. It's about children with poor balance and coordination, who struggle with basic movement skills that we all take for granted.

Dyspraxia/Developmental Coordination Disorder

A good number of children in the UK have dyspraxia: difficulty with movement, balance, and coordination generally. Basically, they have very poor fundamental movement skills.

In the absence of any other diagnosis that would affect motor ability, children with poor movement skills may be diagnosed with Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD). This affects up to six children in every classroom, and is a diagnosis usually given quite late: children's motor skills are still developing aged six or seven e.g. at the more difficult end of human motor activity such as balancing on a narrow beam and other agility or gymnastic activities. For this reason, clumsiness might simply be down to late developers and thus diagnosis is delayed. One physiotherapist I know, whose child was diagnosed with DCD, believes that children with DCD are simply well below average. After all, we can't all be Nadia Comeneci.

Poor movement skills have a profound and devastating impact on children's development and life chances. There is a large body of evidence showing how poor movement skills affect children's physical, emotional, social, psychological and educational development. Researchers have called children with movement difficulties 'onlookers in the playground', and one study found that a large number (80%) of seven year old children with DCD went on to experience drug and alcohol abuse, trouble with the law and mental health difficulties by the age of 22, compared to 11% of the children with typical movement skills. Further evidence also suggests that children’s motor skills have a positive association with physical fitness, body weight and physical activity. Because physical activity tracks across the lifespan, increasing physical activity in childhood can have huge benefits in population health (including mental health) and academic achievement.

In Bradford, a large cohort study (Born in Bradford) has been following over 13,500 children from birth since 2007. During investigations and assessments in schools, we have found that a large proportion of children experience difficulty with their fundamental movement skills. These difficulties have been noted by children's teachers, who have repeatedly asked if there are any exercises that would help these children. For this reason we conducted a systematic review looking for evidence-based activities which could benefit children with poor movement skills. This found nine studies which investigated a total of 16 interventions. Three well-conducted trials in particular found that some physiotherapy activities produced large effect sizes in outcome measures evaluating the children's movement skills.

I have developed these evidence-based activities into a physiotherapy programme designed to be delivered in schools by school staff.

This overcomes the problem for these children of having to wait until formally diagnosed with having a problem before they can be referred for help with physiotherapy or occupational therapy. Besides, there is a sting in the tail for these neglected children because they do not necessarily receive the treatment they so badly need even then. Even before austerity kicked in and reduced numbers of NHS therapists, children with poor movement skills made up 60% of occupational therapy team's waiting lists, and some had to wait up to four years just for an assessment! This is unlikely to have improved in the years of austerity experienced by the NHS since 2007.

Teachers recognise that there is a relationship between poor movement skills, balance and coordination and academic achievement. My qualitative research at a PE teachers and head teachers conference, at meetings with head teachers and from piloting of the evidence-based activities in a school suggests that head teachers and school staff are keen and willing to deliver a programme like this. Indeed, there are already programmes in several schools across the country, but these are not evidence-based or properly evaluated for efficacy.

What are we waiting for!? Let's get it tested !

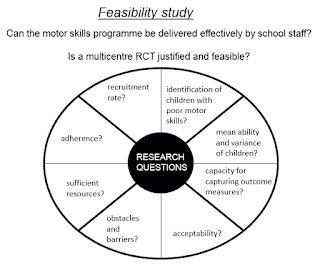

Unfortunately, despite a number of pilots in schools and some work with teachers and non-governmental organisations, I have been unable to secure funding for an appropriate study to evaluate whether the programme can successfully be delivered in schools by school staff. In the long term, a multi-centre randomised controlled trial (RCT) to evaluate the effectiveness of the physiotherapy programme is necessary, but I first need to conduct a feasibility study to find out whether the programme can be delivered at all by school staff. This feasibility study will also gather essential data needed for properly designing the RCT.

This research has follwed the Medical Research Council guidelines for developing complex interventions, a process that includes developing the scientific rationale, conducting a systematic review, piloting and then conducting a full trial if justified. So, according to the NIHR definition, a feasibility study finds out 'can this be done?', and does not necessarily need a randomised element. However, I will be evaluating change in children's movement skills, because if there is no change, then a multi-centre randomised trial will be unnecessary. My colleagues are developing a new measure of fundamental motor skills which I hope will be fully tested and published when this research is eventually conducted.

So, what's the problem?

My funding applications have been rejected at the final hurdle, after passing through earlier stages satisfactorily. This has proved extremely frustrating, especially given that I was confident because of the outstanding advice, support and guidance from my awesome mentors, the NIHR's Research Design Service and some senior professors.

The support and positive feedback of senior and highly respected academics gives me confidence in my research, although it does take a battering. One has to be thick-skinned in academia; with reviewers of applications and papers submitted to journals for peer review protected by anonymity, comments and feedback can be pretty brutal, and often just unprofessional or even occasionally stupid. One reviewer (of an NIHR application) wanted to know what a feasibility study was, even though I had referenced the NIHR's definition and description with every mention of 'feasibility study'.

|

Well, it is a feasibility study. So, it's at the feasibility study stage.

At one interview, I had to explain the purpose of a control group to a professor. Another reviewer was of the opinion that it shouldn't be funded in case the children didn't get faster and their hopes were dashed. I hope that reviewer doesn't review any proposals for research into any promising cancer treatments.

At one interview, I had to explain the purpose of a control group to a professor. Another reviewer was of the opinion that it shouldn't be funded in case the children didn't get faster and their hopes were dashed. I hope that reviewer doesn't review any proposals for research into any promising cancer treatments.

So the process of applying for funding is frustrating, daunting, painful, time-consuming and occasionally surreal. It takes a thick skin, tenacity and a sense of humour. It takes months to complete some applications. Research is hard, getting funding even harder - but life is hard for children with dyspraxia, and I am determined to see the movement skills programme further developed and tested. It could contribute to better lives for disadvantaged children across the UK and beyond, as well as have significant benefits for population health and the economy.